Heritage Blog

Faith, Femininity and Power in the West Window

Evie Brett unpicks the complex imagery of the cathedral’s West Window, exploring its relationship with Victorian England. Depicting the tale of the Ten Foolish Virgins, the West Window is an incredible example of how tales from the bible become interlaced with new meanings within the capacity of our own lives.

November 30, 2023

Seeing Things in a New Light: Ripon’s West Window

Standing opulently, in true Victorian fashion, Ripon Cathedral’s West Window is truly a sight to behold. This sight is made all the better when viewed in the evening sunlight, enhancing the lancet windows’ rich, jewelled tones of blue, crimson and green. Due to the high level of illiteracy of those attending church in the past, stained glass has always been used as an educational tool to visually narrate teachings from the Bible. As such, examples like the West Window demonstrate the multiple uses of imagery, not just as something to be looked at, but also as a functional device for education. Here, the window depicts the parable of ‘The Wise and Foolish Virgins’, exploring the process of preparation for the Day of Judgement and the destinies of Heaven or Hell. The story follows two groups of women, those that are ‘wise’ and prepared for the coming of Christ with lit oil lamps and those who are not, labelled ‘foolish’. Through this imagery, the window illuminates the importance of righteous living in both the past and the present.

It was constructed in 1886 and, as such, also toys with ideas of femininity and womanhood expressed in the Victorian era. When looking at the narrative’s imagery, questions arise about what the window has to tell us about traditional gender roles in this period of history – in both a religious and secular, societal sense. It also opens a wider conversation about the relationship between the Church and the monarch, considering Queen Victoria herself was celebrating her 49th year on the throne when the window was built in 1886! It is only by taking into account this broader story, that we can see the window not just as a flourishing work of Victorian artistry, but as a way to demonstrate how life in 19th-century Britain functioned. Ripon’s West Window forces us to question imagery’s use in the shaping of society and how it can be used to enhance the status of individuals. Using light to illuminate these themes, as if embodied by the light of Christ himself, the stained glass legitimises its own message of power, be it the power of God, or Queen Victoria herself.

The West Window of the cathedral, standing directly above the building’s entrance, was

made by Burlison and Grylls as a memorial to the first two modern Bishops of Ripon:

Charles Longley (1836-1856) and Robert Bickersteth (1857-1884). Though the ten lancet

windows certainly provide a spectacle when viewed as a whole, the narrative of the scene is actually divided into three interrelated segments. The outer two panels on the upper row function as a Victorian version of a Medieval Doom Painting. It shows images of the Last Judgement, where the final resting place of those who have lived on Earth is decided. Those granted salvation march through the gates of Heaven as seen by the words “Come Ye Blessed Of My Father”, while those condemned to an eternity separate God enter through the flaming mouth of a green, evil-eyed monster.

The inner three panels are a selection of images from Psalm 45. A wedding scene, these

windows depict angels playing musical instruments as the bride of Christ surrenders her

worldly goods upon the sacred union. Finally, the lower five windows recount the parable

mentioned before, in which two groups of virgins, or bridesmaids, are seen on their journey to Christ, the bridegroom. An allegory for Heaven, the ten women are split into the ‘wise’ (dressed in blue and green) and the ‘foolish’ (in red and gold drapery), with only the wise remembering oil for their lamps. Whilst the foolish hurry to gather oil from a nearby

merchant, it is only the wise who are prepared for the coming of Christ. They collect the

bride – perhaps an embodiment of salvation – and enter the wedding hall. Light, a common

emblem used for Christ, leads the wise to Heaven, whilst those foolish and disillusioned,

without God in their lives, have the doors to the wedding feast shut before them.

Whilst religion’s importance in 19th century England is the most glowing narrative to shine

through the window, there is also a subtext connecting its three parts. Underlining the

stained glass, runs a theme of marriage and with it the traditional, gender roles operating in Victorian society. Be it the righteous power of God, the monarch or a more general

expectation of loyalty projected onto Victorian women, this window certainly explores

religious, monarchical and patriarchal rule.

The relationship between monarch and God has been a strongly connected one since the

early 17th century. From around 1603, James I published the ‘Divine Right of Kings’; a law

arguing that monarchs derived their authority directly from God, and as such, were his

representatives on earth. The ‘Divine Right’ thus increased the power of a King or Queen to

such an extent that, at times, many viewed monarch and God as two sides of the same coin. Hence, it is quite likely that the West Window’s teachings about loyalty and devotion to Christ, is at the same time a reference to the power and iconic status of Queen Victoria

herself. Much like God, she too asked for faithfulness and loyalty from her subjects.

Though not a direct representation of Victoria, there is strong female monarchical imagery

within the central wedding feast scene. Often described as ‘the Queen of Orphir’, the window’s queen carries a sceptre, is dressed in the finest gold and is accompanied by three attendants. She is pictured on her way to the bridegroom, who sits in majesty on his

heavenly throne and holds an orb symbolising the world. The window is awash with symbols of both religious and monarchical power. It is this mix of symbols of different types of power that so perfectly captures how interconnected monarch and Christ were. Both were considered leaders who ruled over their subjects. Here, the window represents the people’s civil obedience to Victoria as her God-like status as monarch on earth is reflected in the narrative of Christ in Heaven.

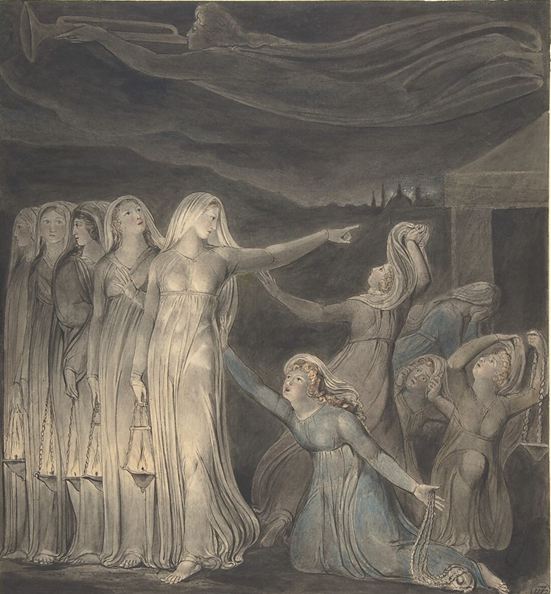

Certainly, whilst the glory of the stained glass as a medium, alongside its imagery, was used to enhance Queen Victoria’s iconic status, this interpretation still leaves an underlying question about womanhood in 19th-century society. It could be argued that there lies an undertone about the passivity and obedience expected of women specifically at this time, including the idea of chastity as a requirement of Victorian femininity. Though made before the window itself, in 1799-1800, William Blake’s watercolour painting ‘The Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins’ provides an excellent visual for connection. Much like the glowing light through the window, Blake’s painting uses contours and shadows to achieve the same luminosity, shrouding the ‘wise’ in a white, incandescent virtue, a further signifier of what was expected from women in the Victorian age.

The Ripon Millenary Record of September 1870 describes how the West Window was “a combination of various geometrical forms with the conventional foliage peculiar to the works of the period”, being executed in “the richest and most varied colours”. Whilst on the surface, the stained glass is first and foremost a rich and vibrant masterpiece, it is also one that uses imagery to explore the connection of religious and monarchical power. Just as the stained glass illuminates the cathedral, it too sheds light on the political context of the Victorian era. And so, its meaning changes depending on the light you see it in!

Article written by Evie Brett, Digital Volunteer