Heritage Blog

Carving the History of Ripon Cathedral

Discover how 7th century multiculturalism influenced the design of the cathedral’s architecture. Digital Volunteer Hannah Labonte explores design in the times of St Wilfrid.

November 30, 2023

Details of Design in the Cathedral’s 7th Century Stone Fragment

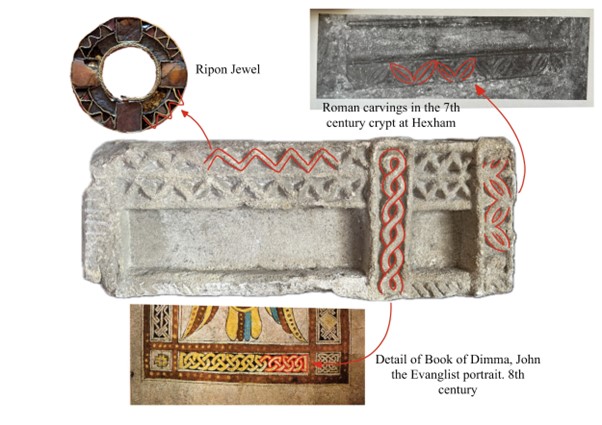

Inside the gothic cathedral that stands today lies the remains of the earliest stone foundations at Ripon. The crypt, which can still be visited, and fragments of decorative and architectural sculpture share with us details of the culture and history of the site nearly 1400 years ago. This fragment of architectural sculpture that this article discusses was found in the crypt during 1900 excavations, and is an excellent example of the cultural fusion that took place on this site as well as in early medieval Britain more generally.

Ripon cathedral stands in the former territory of the Kingdom of Northumbria (654-954). Northumbria in the seventh century was a region that had invited various cultures into its established arts of architecture, manuscripts, and other decorated goods. The impact and influence of three different cultures can be seen in the very fabric of the crypt, and even more specifically in this fragment’s decorative scheme. These influences are: Irish/Celtic, Germanic, and Roman/Classical.

In order to better understand the presence and fusion of these cultures on the sculpted fragment, it is essential to under the context of its carving.

Irish

The Venerable Bede, arguably England’s first Historian, shares in his ‘Ecclesiastical History of the English People’ the significance of the site of Ripon. Before Wilfrid received the lands around Ripon from Alhfrith, the son of King Oswiu, in 660, a thriving monastery already existed on the site. This monastery followed the Irish tradition of Christianity, which was officially replaced in Northumbria by the Roman tradition at the Synod of Whitby in 664. Wilfrid, a follower and representative of the Roman Christianity, then began the construction of his stone church dedicated to St. Peter at Ripon. However, the presence of Irish, or more broadly, Celtic culture did not disappear. On this fragment there is a distinct pattern of interlace that twists from one edge to the other. This pattern can be observed in various Irish or British manuscripts from the period, and is often zoomorphic—meaning it takes the form of an animal. An example can be seen in the Book of Dimma, an eighth century pocket gospel book specifically on the evangelist portrait of John where interlaced patterns border the image of the eagle. When looking at the manuscript and the stone fragment is easy for your eyes to get lost in the twisting and overlapping of the pattern. Following like a maze. This level of intricacy, found in both sculptures and illustrations, is a key example of the sophistication of Irish influenced art in the early Middle Ages. Wilfrid himself was educated at the island monastery of Lindisfarne, which followed the Irish Liturgy, and was likely aware of this art. Although scholarship tends to believe the famous Lindisfarne Gospel was completed in the the decades following Wilfrid death (709) it is highly likely that other great works were produced during Wilfred’s residency there; none of which survive today. The observation of this pattern on the fragment from Wilfrid’s stone church built in 672, demonstrates how even after the Synod of Whitby, elements of Christian Irish art found its way into the fabric of foundations with Roman associations.

Germanic

The ethnic context of Northumbria’s seventh century society is important to understanding the stylistic elements of the art produced in the region. In the fifth and sixth centuries large waves of migrations flowed from northwestern Europe into the British Isles. The northern region of Northumbria was populated by an Angle majority who came from modern day Denmark. These Germanic tribes that now inhabited the area of Britain lived in a largely rural, warrior culture. Much of the art preserved from these peoples are weapony and grave goods, largely crafted from metals. The zig-zag motif found on the stone fragment from Ripon is a feature commonly associated with Germanic style metalwork. The Ripon Jewel, another artefact associated with Anglo-Saxon Ripon, uses this same zig-zag effect around its border. The presence of this feature carved in stone demonstrates yet another connection to the cultural roots of the people who resided in the region.

Rome/Classical

Wilfrid’s famous churches of Hexham and Ripon were constructed using what is commonly referred to as spolia. Literally translated to “spoils of war”, spolia is often used in art and architectural history to describe pieces of one building used in the foundation of another building. While some people argue that it may be due simply to practicality, others argue that the careful selection of pieces to reuse and the expense of transporting the materials would mean that the choice to recycle material was deliberate, and had meaning. The significance of this reuse is often related to the power of the memory that exists in the stones. When discussing Roman spolia in the Northumbrian built environment, the reused stone creates a connection between the power of the newly established Roman Church in Britain, and the Roman Imperial past.

The crypt at Ripon is full of Roman spolia, which leads us to suspect the churches that stood overtop of them were as well. We do not know if the fragment we are looking at was originally placed in the crypt, or whether it was moved there sometime between the eighth and twentieth centuries. What we do know, however, is that this is not a piece of spolia, but rather native stone quarried in Britain. Wilfrid was somewhat of a Romanophile, making three pilgrimages to Rome throughout his lifetime, the first at only 19 years old. He would have been exposed to all sorts of art and sculpture in the holy centre of Europe, and likely used this inspiration when constructing his churches. His biography tells us that he brought back with him foreign masons to help construct his church, since those native to Northumbria were largely unfamiliar with building in stone, but we can’t know if they worked on this fragment of stone specifically. What we can observe through this fragment is a row of foliage carved along the edge. Not only does this feature echo the classical sculptural style of Rome, but also closely resembles a similar carving at Hexham. The Roman influence can be seen in the foliage carving as well as the very material of stone, which was not the typically building material of the Anglo-Saxons, and commonly associated with Rome and the Church during this period.

Summary

These details and their presence on this single fragment of architectural sculpture shared with us, 1400 years later, reveal the multiculturalism that influenced art. In a period of migration, conversion, and change, this artefact demonstrates the artists and masons’ abilities to craft something that recognizes the various groups of people and cultures coexisting in the region.

The original use of this fragment remains unknown. It has been identified as architectural sculpture, or perhaps originally part of a stone piece of furniture. Other hypotheses include it being a section of an altar, a frieze lining a doorway, or some sort of pillar. Its discovery as a step leading out of the crypt has not been ruled out as a possibility: decorated steps were somewhat popular in continental architecture of the period. Perhaps knowing the original placement and purpose of this fragment is not the most important detail. Arguably its very existence in a seventh century crypt or church in Northumbria is important enough, and shares with us—the modern viewer—the artistic influences that shaped the construction of Ripon.

Written by Hannah Labonte, Digital Volunteer