Ripon Book of Hours

Ripon Cathedral Library

Ripon Cathedral’s medieval library was dispersed during Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. When Anthony Higgin was dean (1608-1624), he reassembled a large library. This was full of theological writings, classical works, and more. He left these books to his cousin and nephew and said when they died the books should go to Ripon Cathedral to form a library. The library continued to grow, containing thousands of printed books and several medieval manuscripts. Now the Brotherton Library in Leeds looks after most of the books for the cathedral, along with many more manuscript fragments and medieval documents from the cathedral.

Book-Making in the Middle Ages

Commercial book trades existed in many European cities from the early thirteenth century. Book-making was a collaborative endeavour. It relied on the skills of scribes, illuminators, parchment-makers, and binders. These craftsmen usually lived and worked in cities, often near universities. They formed guilds to regulate standards and competition in the area.

Books of Hours

Books of Hours were one of the most popular books of the Middle Ages. They were first produced in the thirteenth century. This was part of a cultural change towards manuscripts being designed for individual use rather than a community. At first, it was only the wealthy that possessed Books of Hours, and many were produced for women. From the fifteenth century, the mass-production of manuscripts made them more accessible.

Early Books of Hours were entirely written in Latin but from around 1400 some French and English began to appear. Many of the lay people who owned these books were not literate in Latin. However, the language was often familiar from church services. Images also supported their understanding and provided a focus for meditation.

Many Books of Hours have traces of their owners’ personalisation. In some cases, the patrons were even included in the miniatures used to illustrate the book. Others have coats of arms or personal emblems.

The Hours of the Virgin (the main component of books of hours) was divided into a series of short services. The sections corresponded to the eight canonical hours (Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, Compline). These had structured daily prayers for clergy for many years, but Books of Hours helped lay people follow a personal prayer routine too. Individuals could recite the Hours of the Virgin as part of a private prayer life.

The Ripon Book of Hours [Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis]: Ripon Cathedral MS 9

The Ripon Book of Hours was created in the Low Countries around 1350-1400 but was then brought to England. From the outside it looks unassuming, bound in brown leather. But open it up and you’ll see that it was illuminated – elaborated decorated with different coloured inks and precious gold leaf. This required a lot of skills and would have made it expensive to buy.

It has five sections, all in Latin and each with a different role in helping the reader to pray.

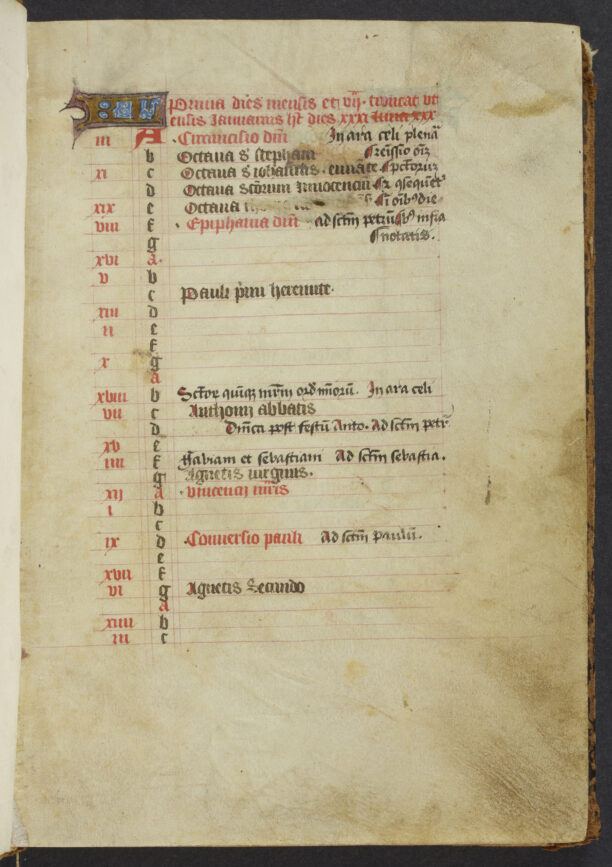

Calendar (folios 1-6)

The Ripon Book of Hours begins with a calendar of feasts. The column of letters from a-g represents the days of the week so that it could be used for different years. The scribe used red to emphasise major festivals. Other writers have added extra information under some months.

Calendars tend to include local festivals. This makes them helpful for working out where a book was produced or used. Additions to the calendar in the Ripon Book of Hours suggest it was used by Franciscans before it made its way to Ripon. It was used in England by the late fifteenth century as obits were also added for Edward IV and Henry VII.

Hours of the Virgin (folios 7-28)

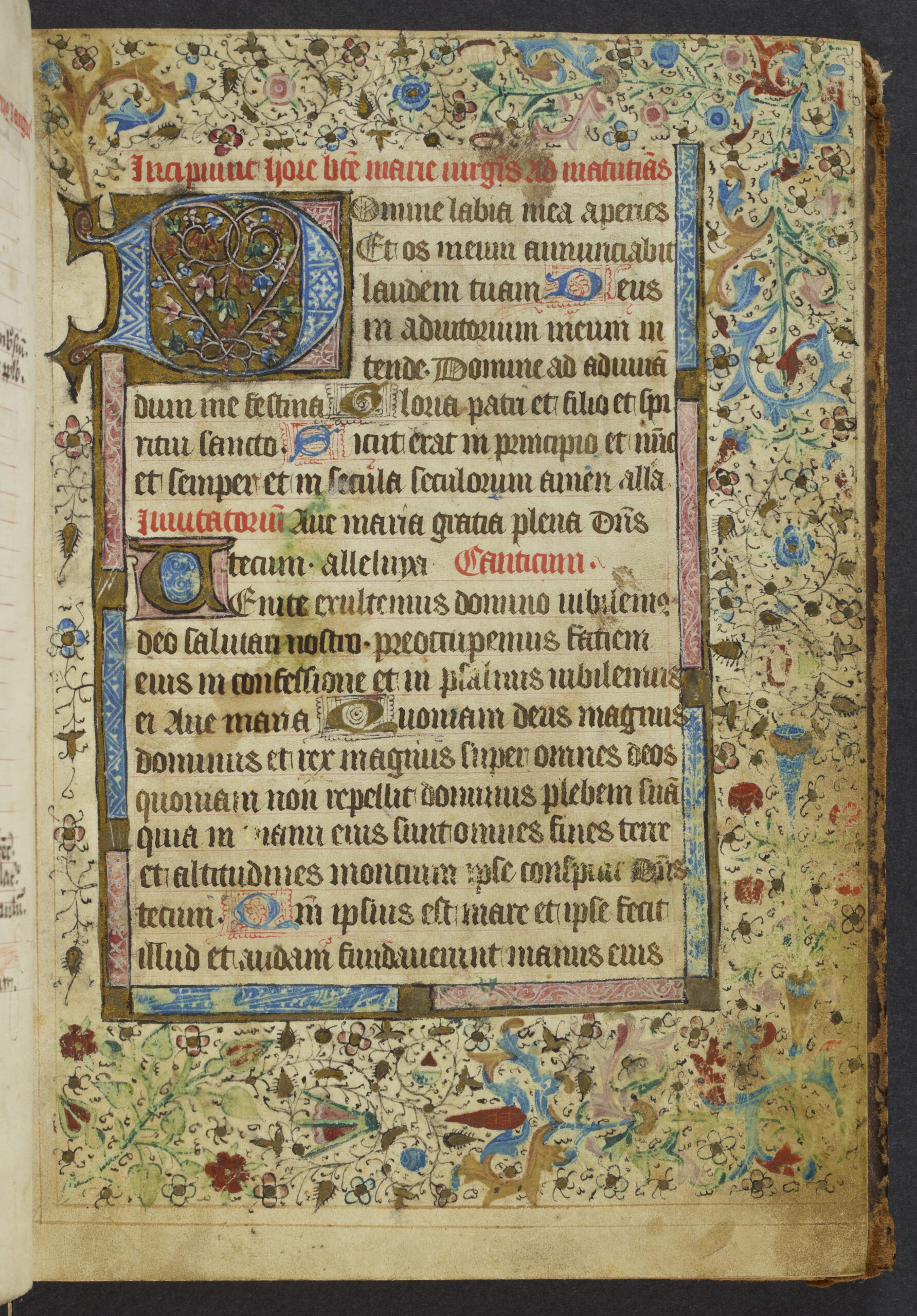

The Hours of the Virgin was the core text of Books of Hours. Prayers were arranged into eight canonical hours, spread throughout the day. This helped lay people to pray in a similar fashion to monks and nuns. The Hours focused on Mary, who was seen as an intercessor to help people to pray effectively.

The elaborate border indicates that this was the start of a new section of the manuscript. The writing in red at the top tells the reader what the section was. Each section begins this way, except for the Psalter of St. Jerome where the first page is missing!

The border is made up of a filigree band of blue, rose, and gold, surrounded by a floral border. The flowers include poppies, daisies, and trumpet flowers. You might also spot ivy leaves, pinecones, and quatrefoils (a shape resembling four circular leaves). The use of gold leaf for the initials and in the border shows that the patron must have been wealthy.

Saul’s Suicide

A large and elaborate ‘D’ is used for ‘Domine’ meaning Lord. Large, decorated initials were often used for the start of a new and important section. Here, it is used to begin the first prayer. The prayer starts by asking God to open the person’s lips so their mouth will declare God’s praises.

Smaller illuminated initials are used for the first letter of a new sentence and medium-sized ones are used for a new paragraph or subsection.

Penitential Psalms and Litany (folios 29-37)

There were seven penitential psalms, which medieval people attributed to King David in his penance for the sins he had committed. These aimed to help people confess their sin and ask for God’s forgiveness.

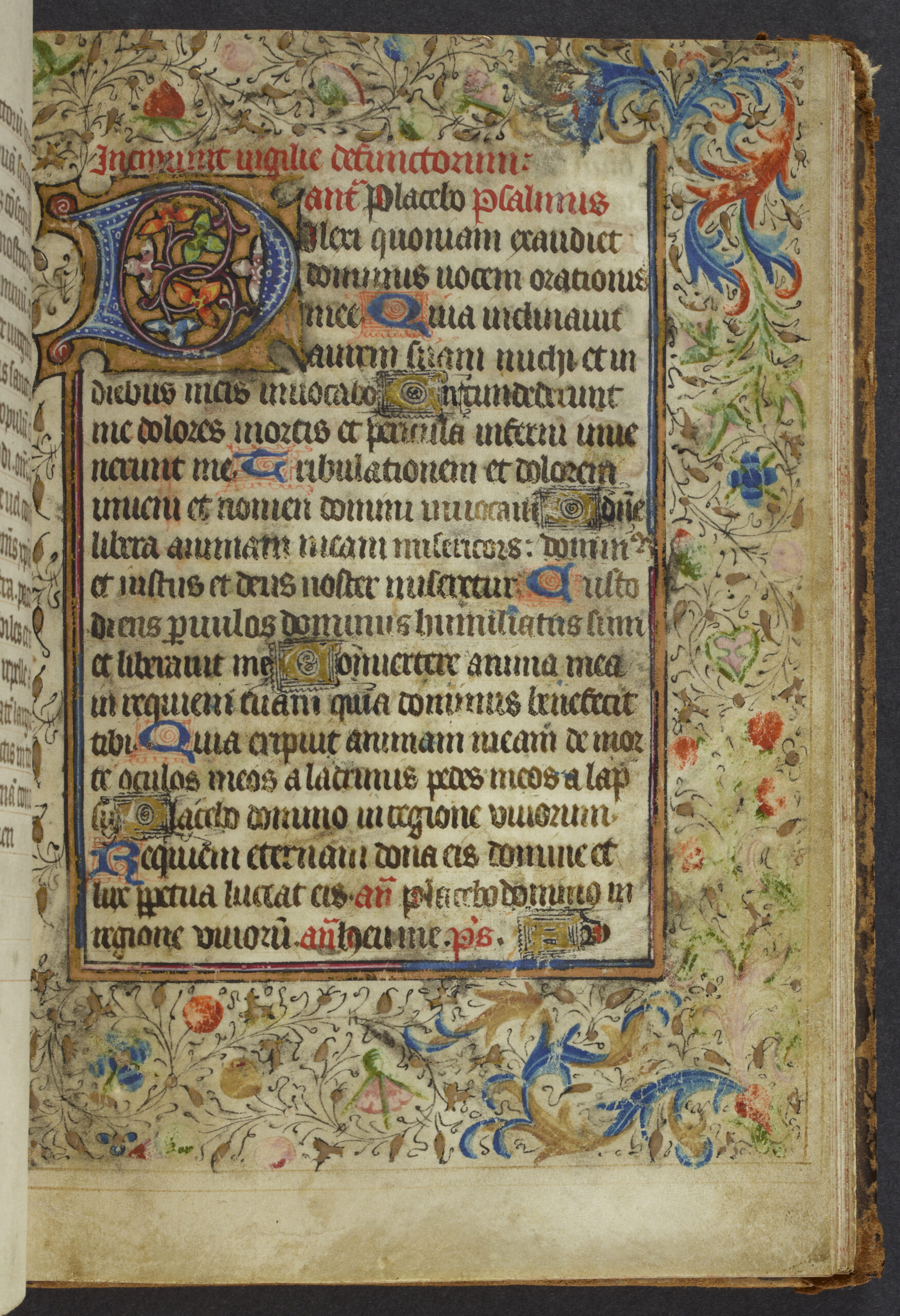

The illuminated letter ‘D’ is used for ‘Domine’ again here but here it is filled with quatrefoils within a diamond pattern. The border is in a similar style to the start of the Hours of Virgin, but it is not identical.

Here, you can see the border is smudged on the right-hand side, most likely from people turning the page.

The Litany was a series of prayers petitioning the saints. It was usually recited by the clergy and the congregation replied. In this section, the reader addresses a series of saints, including Mary, Michael, John the Baptist, Peter, and Paul.

The response at the end of the line ‘or’ is short for ‘orate pro nobis’ meaning ‘pray for us.’

This version has a page missing so has lost some of the prayers to the apostles.

Office of the Dead (folios 38-56)

This was a series of prayers for those who had died. It was believed that if people died without having all their sins forgiven then they would go to Purgatory until they had been cleansed from those sins. They thought that prayer could help souls to move from Purgatory to Heaven more quickly.

For those who could afford it, it was common to pay for masses to be said for the souls of family members who had died.

Reciting these prayers also helped the reader to prepare for their own death and to contemplate The Last Judgement.

Psalter of St Jerome (folios 57-64)

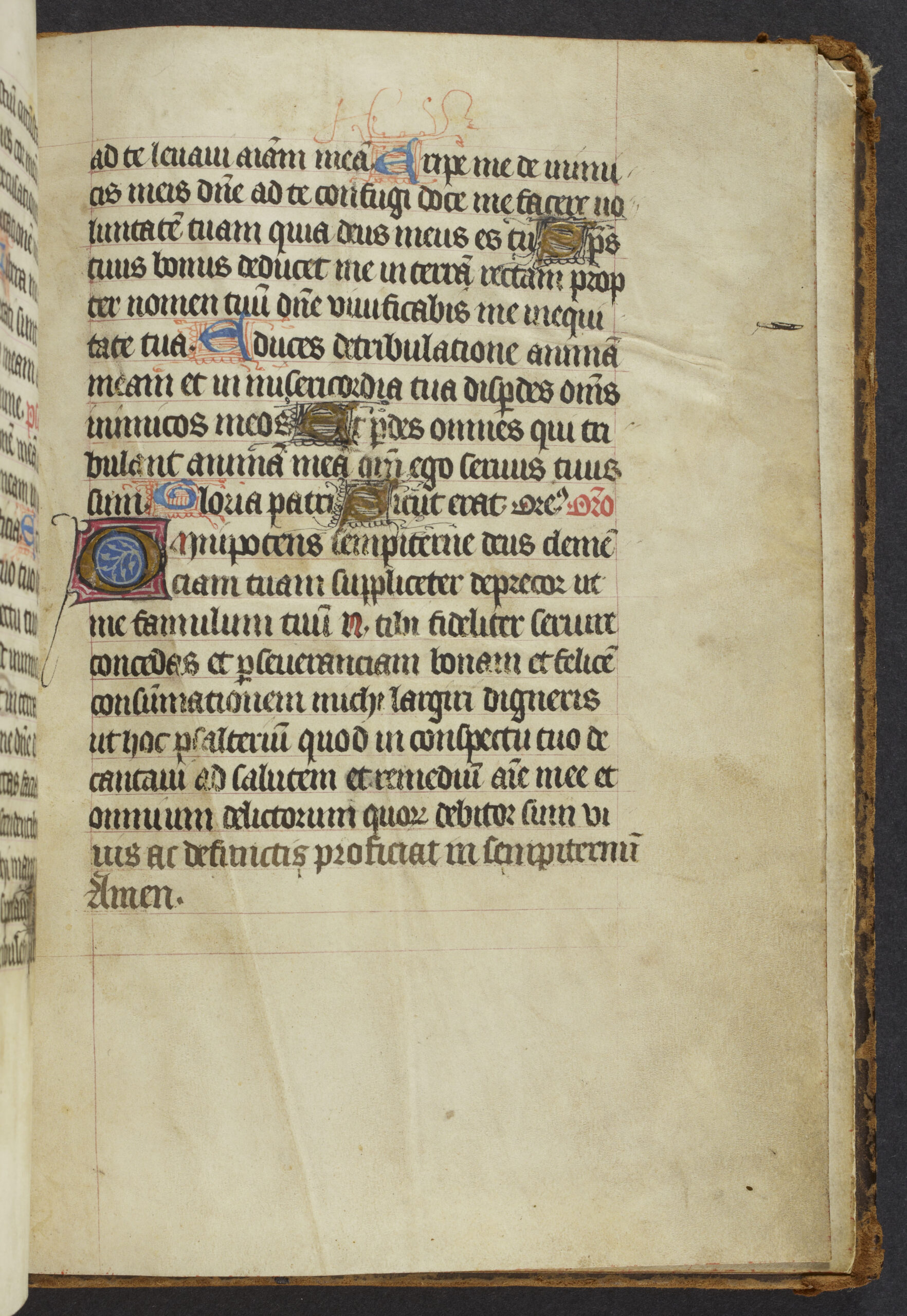

The final section is a collection of Psalms arranged by St. Jerome. This one was of the most widely used arrangements of Psalms in the Middle Ages. Its creator, Jerome, was a Catholic priest in the late 4th and early 5th centuries. He also translated the Bible into Latin and wrote many commentaries on Scripture.

The Psalter doesn’t distinguish between separate Psalms. Individual verses begin with an illuminated initial but the verses from different Psalms follow one after the other.